FROM AESTHETIC BEAUTY TO ETHICAL BEAUTY

“They always say time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself.”

Andy Warhol.

Since the start of the year, professional and social conversations (duly distanced, of course) in addition to numerous post titles have been dominated by the issue of post-COVID consumption, the looming changes, new consumption guidelines and the trends consumers will follow.

Experts are debating two theories for the coming years.

Some believe we’ll see part two of the Roaring Twenties and everything that involves: hedonism, excess, consumption, fun and enjoyment at the heart of our priorities.

Others, however, are predicting a much calmer period during which the after effects of social distancing will translate to fear of a new potential threat, even among young people, and where the screen will continue to be a frequently used aspect in social events (for example, the gym and language schools) and occupational scenarios.

Flexibility, working fewer hours, earning less and prioritising health, comfort and a more sustainable life will be valued.

Which stance best reflects the short/medium/long-term reality? Both will almost certainly apply to a specific point in time as well as the age and aspirations of each person.

Obviously the next two, three or more years will see trends accelerated as we know crisis means opportunity, the need to sharpen ingenuity and, as ‘The Art of War’ preaches, “opportunities multiply as they are seized”.

But the important issue is that to know where we’re headed, we need to reflect on where we’ve come from.

And, What does beauty have to do with all of this?

Everything.

According to Gilles Lipovetsky (the hypermodernity philosopher), a new species of hominid has been developing on the planet for more than a century:

The Homo Aestheticus.

Its most relevant characteristic is its aesthetic attitude to life: a constant desire to invent itself, to obtain immediate sensations; one who loves to please the senses, binge on new things, fun, quality of life and self-realisation.

Its natural habitat is also masterfully described by Lipovetsky as Aesthetic Capitalism, where it’s almost impossible to distinguish between art and economy.

Beauty and its transaesthetic dimension seeps into every aspect of life: daily objects, decoration, fashion, culture, leisure, food, personal care. And it develops in line with economic rationale, marketing, series, multiplicity, accelerated expiry and constant renovation.

In 1962, Andy Warhol created what’s known as the art business by painting a series of works depicting objects taken from supermarket shelves, including the famous tin of soup.

His many famous phrases include, “commercial art is much better than art for art’s sake”, and not only did he become rich and famous, as he wanted, by painting bananas, detergents and tins of soup, but he was also declared one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. His paintings are auctioned off for impressive amounts at Sotheby’s.

Three decades later, Philippe Starck designed a citrus fruit juicer that has sold more than 350 million units. It’s on display in the MOMA in New York and has made the front cover of a book titled ‘Emotional Design’. Not functional or industrial design; not even sustainable design. A juicer is classed as an emotional object.

So, what is art? What is its goal? What is its culture? What is its industry?

I’m just a copier, an impostor.

I wait, I read magazines.

After a while, my brain sends me a product.

Philippe Stark

If the Starck juicer is in the MOMA and home décor shops around the world, does that mean taking a walk through Le Bon Marché (designed by Eiffel) or the wonderful Hermès Rive Gauche store, situated in what was a swimming pool in the 30s, constitutes shopping or culture?

Is travelling synonymous with culture, even if we choose perfectly designed experiences like hotels, restaurants and excursions? Does the Apple Store only offer consumerism or is there a concept? Is the almost mandatory weekly visit to Zara maybe not as comparable to leisure as an aperitif on Saturdays?

Going back to Lipovetsky: “beauty isn’t a luxury, it’s written in the living”.

Seduction is how it tends to develop in the society of Aesthetic Capitalism. And we love being seduced because it makes us feel better.

Since the first temples of shopping, mannequins and shop windows were created, leisure, seduction, beauty and economics have gone hand-in-hand.

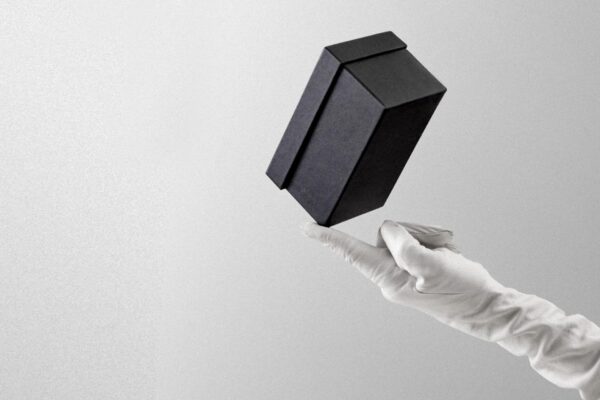

Shop windows, packaging and advertising transform people’s relationships with objects. They reduce the tactile relationship with things but intensify the visual relationship with them, and they feed it through design and aesthetics in a bid to seduce.

Since then (the end of the 19th century) the mediums have multiplied: television, computers, smartphones… But the shop window principle is the same.

The result: today, seduction dominates almost the entire world.

And in this new post-COVID world:

Do we want to stop being seduced?

Are we ready to type into Google, for example, “juicer” and only see three industrial models with no hint of aesthetic or emotional intentions?

Are luxury and consumerism in general the “devil” of sustainability?

Are we going to stop travelling for pleasure to the antipodes of our place of residence to save the planet?

Are we ready to stop updating technology constantly?

Or will we conform with environmentalism as social posturing?

Will the trend of “buy less, buy better” go any further?

It’s complicated, right?

Realising that this desire for “the new” has transcended advertising or marketing to become a social anthropology or modernity issue appears to leave us little chance for change.

However, it depends, in part, on us – “the seducers” – to offer solutions or direct the way in which things operate.

I can think of the following ways to operate this change:

- Focus more on the innovation of real impact (which affects processes and materials) and not on innovation that only focuses on visual perception.

- Don’t be afraid of changing visual or aesthetic codes. If the world lost its mind with Warhol’s bananas, we can be successful by showing things from new standpoints.

- If marketing is anthropology, we need anthropologists; if design is art, we need artists; if consumption is culture, we need sociologists.

All these profiles – many of which are at risk of becoming extinct – will be necessary in companies of the future because seduction and luxury are turning towards critical conscience. We’re not going to consume less but we are going to look more carefully at what we buy.

And we need them to work alongside engineers, industrial and graphic designers, data experts, supply chain managers and more. It’s not merely about reflecting, but rather it’s about guiding reflection for a specific purpose.

- Question everything and don’t be afraid of constructive criticism.

- Be authentic, even if it makes it slower to reach the top.

- Worry about the world we’re going to leave behind for future entrepreneurs, as well as the kinds of companies we’ll leave the world for the future.

It’s not easy because, going back to what I said at the start, it’s true that there’s a change behind this crisis but we don’t know how to describe it particularly well, nor do we truly know which direction it’s going to take us in. But let’s hope it makes us better, more committed professionals.

Carmen Yago, Marketing & ESG Director at Salinas Packaging Group

References:

Lipovetsky, Gilles & Serroy, Jean. L’estethisation du monde. Vivre a l’age du capitalisme artiste. Paris: Gallimard, 2013

Netflix. Made You Look (documentary)

Filmin. La Casa de Cardin (documentary)

Youtube. ‘Bon Marché: les coulisses du premier grand magasin au monde’ (documentary)